Laozi's had a most famous follower, Zhuang Zi.

In general, Zhuangzi's philosophy arguing that our life is limited and things to know are unlimited.

To use the limited to pursue the unlimited, he said, was foolish. Our language, cognition, etc. are all biased with our own perspective so we should be hesitant in concluding that our conclusions are equally right for all things (wanwu).

We must be wary of our tendency to adopt fixed or dogmatic judgments, evaluations, and standards based on a narrow viewpoint, since this leads to conflict and frustration

Zhuangzi's thought can also be considered a precursor of multiculturalism and pluralism of systems of value. His pluralism even leads him to doubt the basis of pragmatic arguments (that a course of action preserves our lives) since this presupposes that life is good and death bad. In the fourth section of "The Great Happiness" (至樂 zhìlè, the eighteenth chapter of the book), Zhuangzi expresses pity to a skull he sees lying at the side of the road. Zhuangzi laments that the skull is now dead, but the skull retorts, "How do you know it's bad to be dead?"

Another example points out that there is no universal standard of beauty. This is taken from the chapter "On Arranging Things", also called "Discussion of Setting Things Right" or, in Burton Watson's translation, "Discussion on Making All Things Equal" (齊物論 qí wù lùn, the second chapter of the book):

Mao Qiang and Li Ji [two beautiful courtesans] are what people consider beautiful, but if fish see them they will swim into the depths; if birds see them, they will fly away into the air; if deer see them, they will gallop away. Among these four, who knows what is rightly beautiful in the world?

One of his well-known part of the book is also found in the chapter "On Arranging Things".

One of his well-known part of the book is also found in the chapter "On Arranging Things". This section, which is usually called "Zhuangzi dreamed he was a butterfly" (莊周夢蝶 Zhuāng Zhōu mèng dié), relates that one night Zhuangzi dreamed that he was a carefree butterfly flying happily.

After he woke up, he wondered how he could determine whether he was Zhuangzi who had just finished dreaming he was a butterfly, or a butterfly who had just started dreaming he was Zhuangzi. It hints at many questions in the philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, and epistemology. The name of the passage has become a common Chinese idiom, and has spread into Western languages as well.

Zhuangzi's philosophy was very influential in the development of Chinese Buddhism, especially Chan, and Zen which evolved out of Chan. Zhuangzi's points about the limitations of language and the importance of being spontaneous, in particular, were strongly influential in the development of Chan.

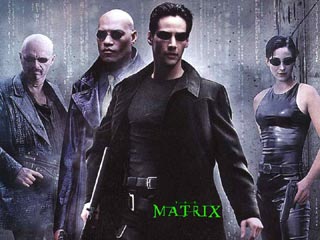

Note: The film, "Matrix" used some of these thinking from ZhuangZi. When we woke up, is it a dream or reality? Are we dreaming the things we did are real or in our dream?

No comments:

Post a Comment